When Teams and Mental Models Collide

By Susan Wilkinson from Unsplashed

I’ve been thinking a lot about mental models lately. For obvious reasons if you’ve seen some of my recent posts on LinkedIn.

When two teams/organizations/companies/business are merged, there will be confusion and conflict. This is natural and unavoidable. The question is how you push through it. Some of this will certainly be based on personality. Some of this may be about culture and values — or the culture and values of the current leaders — or the ghosts of past leaders, that may have left months or even years ago.

Some of this is about incentives and values and roles and responsibilities, the team size and composition, and the history. The stories that are told. Stories capture the struggles, lessons, and challenges that are overcome and celebrated by teams. These stories must be shared and celebrated. What is a teams “origin story?” What is their proudest moment over the last quarter or year? Does the team value heroics and fire-fighting or strive for a more sustainable pace? Some of this may be about age, gender, or even parental status. Most of us in our fifties don’t want to hustle (or don’t feel like we need to) the way we did in our twenties or early thirties.

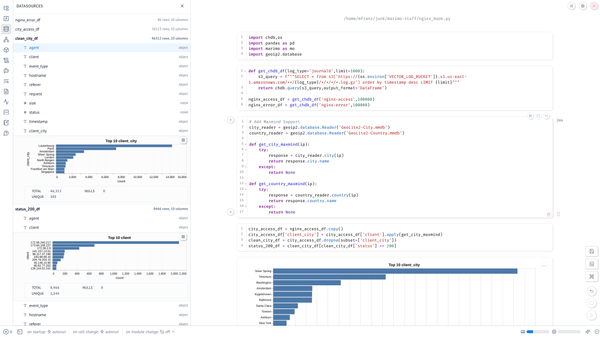

Another key factor is whether there was a scarcity mindset. What resources were available to the team? Was there the ability to purchase commercial tools and services? What was built vs. bought vs. outsourced? These constraints forced logical decisions and actions that might seem foreign to those that did not have those constraints. Of course, you will be confused if you don’t have the context. It will not make sense.

So I’m starting to think there is something more fundamental going on in terms of how different organizations view their work and the problem space and what they optimize for based on their environment and what was demanded or not demanded of them as individuals or a team.

The mental models are different. This is deeper and more fundamental than the words that are used that might not be understood or used the same way.

I am reminded of the difference between on premise software and cloud delivery, which I encountered this in the last decade.

There are dramatically different mental models for these two different modes.

On Premise software assumes a less frequent release cadence, a different packaging and delivery mechanism. There are software laws of physics in terms of how and when releases can occur. What a release means for an an On Prem product simply might not make sense for SaaS delivery. Developers develop locally with their IDE and a local database. Easy. The application is monolithic and can be run independently in the way that a microservices platform cannot. Developers will resist understanding of the underlying infrastructure that spans their local laptop because it does not fit their mental model of compute and data. They will not care.

I’ve also seen this as well when hardware companies that physically ship products (appliances, dongles, cards, etc.) go down the path of cloud service development and delivery. There is confusion and frustration across fulfillment teams. What constitutes a release that requires full PMO involvement? How do we name and version a thing? What is exposed to the customer or not? How do we support customers? What is a customer? What is an SLA?

I’ve also seen the struggle for those to get the idea of “as Code.” Or for those to get the idea of imperative vs. declarative infrastructure.

These are all questions of mental models. Until you grasp the idea of a desired state that must be maintained (and perhaps defined in a DSL, or something horrible like YAML) you will struggle. Bash has a different mental model than Ansible. Checking your configurations of an application into a SCM vs. pointing and clicking through a UI have different mental models.

At this point it is premature to know what the answers are, but I am certain that to move through a collision of mental models requires patience and curiosity — and most importantly, empathy so you can meet others where they are and NOT resist the opposing models.

There must be a genuine struggle with these abstractions — and not prematurely collapsing or combining conflicting models.

I’m wondering of the tools of ethnography and anthropology might be useful for teams and organizations. For example, what are the underlying structures that inform how teams operate: power distance, time, individualism vs. collectivism, tolerance for ambiguity? There is data and research on organizational cultures and how global teams work that shows there are clear differences and help us understand what is going on.

I guess I’ll need to crack open Edgar Shein and Geert Hefstede again!